Malusoeum of Halicarnassus

Malusoeum of Halicarnassus

Seven Quick Facts |

| Location: Halicarnassus (Modern Bodrum, Turkey) |

| Built: Around 350 B.C. |

| Function: Tomb for the City King, Mausolus |

| Destroyed: Damaged by earthquakes in 13th century A.D. . Final destruction by Crusaders in 1522 A.D. |

| Size: 140 feet (43m) high. |

| Made of: White Marble |

| Other: Built in a mixture of Egyptian, Greek and Lycian styles |

Video: In Honor of the King: The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus

In 377 B.C., the city of Halicarnassus was the capitol of a small kingdom along the Mediterranean coast of Asia Minor. It was in that year the ruler of this land, Hecatomnus of Mylasa, died and left control of the kingdom to his son, Mausolus. Hecatomnus, a local satrap to the Persians, had been ambitious and had taken control of several of the neighboring cities and districts. Then Mausolus during his reign extended the territory even further so that it eventually included most of southwestern Asia Minor.

Mausolus, with his queen Artemisia, ruled over Halicarnassus and the surrounding territory for 24 years. Though he was descended from the local people, Mausolus spoke Greek and admired the Greek way of life and government. He founded many cities of Greek design along the coast and encouraged Greek democratic traditions. Mausolus's Death.

Then in 353 B.C. Mausolus died, leaving his queen Artemisia, who was also his sister, broken-hearted (It was the custom in Caria for rulers to marry their own sisters). As a tribute to him, she decided to build him the most splendid tomb in the known world. It became a structure so famous that Mausolus's name is now associated with all stately tombs throughout the world through the word mausoleum. The building, rich with statuary and carvings in relief, was so beautiful and unique it became one of theSeven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Artemisia decided that no expense was to be spared in the building of the tomb. She sent messengers to Greece to find the most talented artists of the time. These included architects Satyros and Pytheos who designed the overall shape of the tomb. Other famous sculptors invited to contribute to the project were Bryaxis, Leochares, Timotheus and Scopas of Paros (who was responsible for rebuilding the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, another of the wonders). According to the historian Pliny Bryaxis, Leochares, Timotheus and Scopas each took one side of the tomb to decorate. Joining these sculptors were also hundreds of other workmen and craftsmen. Together they finished the building in the styles of three different cultures: Egyptian, Greek and Lycian.

The tomb was erected on a hill overlooking the city. The whole structure sat in the center of an enclosed courtyard on a stone platform. A staircase, flanked by stone lions, led to the top of this platform. Along the outer wall of the courtyard were many statues depicting gods and goddesses. At each corner stone warriors, mounted on horseback, guarded the tomb.

At the center of the platform was the tomb itself. Made mostly of marble, the structure rose as a square, tapering block to about one-third of the Mausoleum's 140 foot height. This section was covered with relief sculpture showing action scenes from Greek myth/history. One part showed the battle of the Centaurs with the Lapiths. Another depicted Greeks in combat with the Amazons, a race of warrior women. On top of this section of the tomb thirty-six slim columns rose for another third of the height. Standing in between each column was another statue. Behind the columns was a solid block that carried the weight of the tomb's massive roof.

The roof, which comprised most of the final third of the height, was in the form of a stepped pyramid with 24 levels. Perched on top was the tomb's penultimate work of sculpture craved by Pytheos: Four massive horses pulling a chariot in which images of Mausolus and Artemisia rode.

The City in Crisis

Soon after construction of the tomb started Artemisia found herself in a crisis. Rhodes, an island in the Aegean Sea between Greece and Asia Minor, had been conquered by Mausolus. When the Rhodians heard of his death, they rebelled and sent a fleet of ships to capture the city of Halicarnassus. Knowing that the Rhodian fleet was on the way, Artemisa hid her own ships at a secret location at the east end of the city's harbor. After troops from the Rhodian fleet disembarked to attack, Artemisia's fleet made a surprise raid, captured the Rhodian fleet, and towed it out to sea.

Artemisa put her own soldiers on the invading ships and sailed them back to Rhodes. Fooled into thinking that the returning ships were their own victorious navy, the Rhodians failed to put up a defense and the city was easily captured, quelling the rebellion.

Artemisa lived for only two years after the death of her husband. Both would be buried in the yet unfinished tomb. According to Pliny, the craftsmen decided to stay and finish the work after their patron died "considering that it was at once a memorial of their own fame and of the sculptor's art." The Mausoleum overlooked the city of Halicarnassus for many centuries. It was untouched when the city fell to Alexander the Great in 334 B.C. and was still undamaged after attacks by pirates in 62 and 58 B.C.. It stood above the city ruins for some 17 centuries. Then a series of earthquakes in the 13th century shattered the columns and sent the stone chariot crashing to the ground. By 1404 A.D. only the very base of the Mausoleum was still recognizable.

Destruction by the Crusaders

Crusaders, who had little respect for ancient culture, occupied the city from the thirteen century onward and recycled much of the building stone into their own structures. In 1522 rumors of a Turkish invasion caused Crusaders to strengthen the castle at Halicarnassus (which was by then known as Bodrum) and some of the remaining portions of the tomb were broken up and used within the castle walls. Indeed, sections of polished marble from the tomb can still be seen there today.

At this time a party of knights entered the base of the monument and discovered the room containing a great coffin. Deciding it was too late to open it that day, the party returned the next morning to find the tomb, and any treasure it may have contained, plundered. The bodies of Mausolus and Artemisia were missing, too. The Knights claimed that Moslem villagers were responsible for the theft, but it is more likely that some of the Crusaders themselves plundered the graves.

Before grounding much of the remaining sculpture of the Mausoleum into lime for plaster, the Knights removed several of the best works and mounted them in the Bodrum castle. There they stayed for three centuries. At that time the British ambassador obtained several of the statutes from the castle, which now reside in the British Museum.

Remains Located by Charles Newton

In 1846 the Museum sent the archaeologist Charles Thomas Newton to search for more remains of the Mausoleum. He had a difficult job. He didn't know the exact location of the tomb, and the cost of buying up all the small parcels of land in the area to look for it would have been astronomical. Instead, Newton studied the accounts of ancient writers like Pliny to obtain the approximate size and location of the memorial, then bought a plot of land in the most likely location. Digging down, Newton explored the surrounding area through tunnels he dug under the surrounding plots. He was able to locate some walls, a staircase, and finally three of the corners of the foundation. With this knowledge, Newton was able to figure out which additional plots of land he needed to buy.

Newton then excavated the site and found sections of the reliefs that decorated the wall of the building and portions of the stepped roof. Also, a broken stone chariot wheel from the sculpture on the roof, some seven feet in diameter, was discovered. Finally, he found two statues which he believed were the ones of Mausolus and Artemisia which had stood at the pinnacle of the building. Ironically, the earthquake the toppled them to the ground saved them. They were hidden under sediment and thus avoided the fate of being pulverized into mortar for the Crusaders castle.

Today these works of art stand in the Mausoleum Room at the British Museum. There the images of Mausolus and his queen forever watch over the few broken remains of the beautiful tomb she built for him.

Colossus of Rhodes

Seven Quick Facts |

| Location: Island of Rhodes (Modern Greece) |

| Built: Between 292 - 280 BC |

| Function: Commemorate War Victory |

| Destroyed: 226 BC by an earthquake |

| Size: Height without 50 foot pedestal was 110 ft. (30m) |

| Made of: Bronze plates attached to iron framework |

| Other: Made in the shape of the island's patron god Helios |

Video: Destruction of the Great Colossus

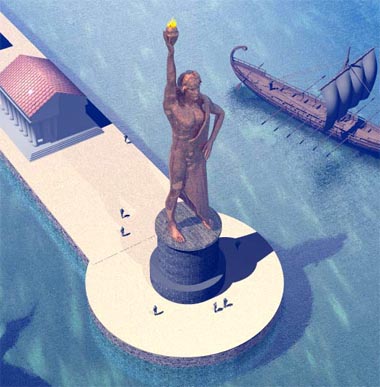

Travelers to the New York City harbor see a marvelous sight. Standing on a small island in the harbor is an immense statue of a robed woman, holding a book and lifting a torch to the sky. The statue measures almost one-hundred and twenty feet from foot to crown. It is sometimes referred to as the "Modern Colossus," but more often called the Statue of Liberty.

This awe-inspiring statue was a gift from France to America and is easily recognized by people around the world. What many visitors to this shrine to freedom don't know is that the statue, the "Modern Colossus," is the echo of another statue, the original colossus, that stood over two thousand years ago at the entrance to another busy harbor on the Island of Rhodes. Like the Statue of Liberty, this colossus was also built as a celebration of freedom. This amazing statue, standing the same height from toe to head as the modern colossus, was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

The Island of Rhodes

The island of Rhodes was an important economic center in the ancient world. It is located off the southwestern tip of Asia Minor where the Aegean Sea meets the Mediterranean. The capitol city, also named Rhodes, was built in 408 B.C. and was designed to take advantage of the island's best natural harbor on the northern coast.

In 357 B.C. the island was conquered by Mausolus of Halicarnassus (whose tomb is one of the other Seven Wonders of the Ancient World) but fell into Persian hands in 340 BC and was finally captured by Alexander the Great in 332 BC. When Alexander died of a fever at an early age, his generals fought bitterly among themselves for control of Alexander's vast kingdom. Three of them, Ptolemy, Seleucus, and Antigous, succeeded in dividing the kingdom among themselves. The Rhodians supported Ptolemy (who wound up ruling Egypt) in this struggle. This angered Antigous who in 305 BC sent his son Demetrius to capture and punish the city of Rhodes.

The War with Demetrius

The war was long and painful. Demetrius brought an army of 40,000 men. This was more than the entire population of Rhodes. He also augmented his force by using Aegean pirates.

The city was protected by a strong, tall wall and the attackers were forced to use siege towers to try and climb over it. Siege towers were wooden structures that could be moved up to a defender's walls to allow the attackers to climb over them. While some were designed to be rolled up on land, Demetrius used a giant tower mounted on top of six ships lashed together to make his attack. This tower, though, was turned over and smashed when a storm suddenly approached, causing the battle to be won by the Rhodians.

Demetrius had a second super tower built and called it the Helepolis which translates to "Taker of Cities." This massive structure stood almost 150 feet high and some 75 feet square at the base and weight 160 tons. It was equipped with many catapults and skinned with wood and leather to protect the troops inside from archers. It even carried water tanks that could be used to fight fires started by flaming arrows. This tower was mounted on iron wheels and it could be rolled up to the walls under the power of 200 soldiers turning a large capstan.

When Demetrius attacked the city, the defenders stopped the war machine by flooding a ditch outside the walls and miring the heavy monster in the mud. By then almost a year had gone by and a fleet of ships from Egypt arrived to assist Rhodes. Demetrius withdrew quickly, leaving the great siege tower where it was. He signed a peace treaty and called his siege a victory as Rhodes agreed to remain neutral in his war against Ptolemy.

Statue Commemorates Victory

The people of Rhodes saw the end of conflict differently, however. To celebrate their victory and freedom, the people of Rhodes decided to build a giant statue of their patron god Helios. They melted down bronze from the many war machines Demetrius left behind for the exterior of the figure and the super siege tower became the scaffolding for the project. Although some reportedly place the start of construction as early as 304 BC it is more likely the work started in 292 BC. According to Pliny, a historian who lived several centuries after the Colossus was built, construction took 12 years.

The statue was one hundred and ten feet high and stood upon a fifty-foot pedestal near the harbor entrance perhaps on a breakwater. Although the statue has sometimes been popularly depicted with its legs spanning the harbor entrance so that ships could pass beneath, it was actually posed in a more traditional Greek manner. Historians believe the figure was nude or semi-nude with a cloak over its left arm or shoulder. Some think it was wearing a spiked crown, shading its eyes from the rising sun with its right hand, or possibly using that hand to hold a torch aloft in a pose similar to one later given to the Statue of Liberty.

No ancient account mentions the harbor-spanning pose and it seems unlikely the Greeks would have depicted one of their gods in such an awkward manner. In addition, such a pose would mean shutting down the harbor during the construction, something not economically feasible.

When the statue was finished it was dedicated with a poem:

To you, o Sun, the people of Dorian Rhodes set up this bronze statue reaching to Olympus, when they had pacified the waves of war and crowned their city with the spoils taken from the enemy. Not only over the seas but also on land did they kindle the lovely torch of freedom and independence. For to the descendants of Herakles belongs dominion over sea and land.

Engineering the Statue

The statue was constructed of bronze plates over an iron framework (very similar to the Statue of Liberty which is copper over a steel frame). According to the book of Pilon of Byzantium, 15 tons of bronze were used and 9 tons of iron, though these numbers seem low to modern architects. The Statue of Liberty, roughly of the same size, weighs 225 tons. The Colossus, which relied on weaker materials, must have weighed at least as much and probably more.

Ancient accounts tell us that inside the statue were several stone columns which acted as the main support. Iron beams were driven into the stone and connected with the bronze outer skin. Each bronze plate had to be carefully cast then hammered into the right shape for its location in the figure, then hoisted into position and riveted to the surrounding plates and the iron frame.

Some stories say that a massive earthen ramp was used to access the statue during construction. Modern engineers, however, calculate that such a ramp running all the way to the top of the statue would have been too massive to be practical. This lends credence to stories that the wood from the Helepolis seige engine was reused to build a scaffolding around the statue while it was being assembled.

The architect of this great construction was Chares of Lindos, a Rhodian sculptor who was a patriot and fought in defense of the city. Chares had been involved with large scale statues before. His teacher, Lysippus, had constructed a 60-foot high likeness of Zeus. Chares probably started by making smaller versions of the statue, maybe three feet high, then used these as a guide to shaping each of the bronze plates of the skin.

It is believed Chares did not live to see his project finished. There are several legends that he committed suicide. In one tale he has almost finished the statue when someone points out a small flaw in the construction. The sculptor is so ashamed of it he kills himself.

In another version the city fathers decide to double the height of the statue. Chares only doubles his fee, forgetting that doubling the height will mean an eightfold increase in the amount of materials needed. This drives him into bankruptcy and suicide.

There is no evidence that either of these tales is true, however.

Collapse of the Colossus

The Colossus stood proudly at the harbor entrance for some fifty-six years. Each morning the sun must have caught its polished bronze surface and made the god's figure shine. Then an earthquake hit Rhodes in 226 BC and the statue collapsed. Huge pieces of the figure lay along the harbor for centuries.

A computer simulation suggests that the shaking of the earthquake made the rivets holding the bronze plates together break. At first only a few weak ones gave way, but when they failed the remaining stress was transferred to the surviving rivets, which then also failed in with a cascading effect. Though some accounts related that the statue fell over and broke apart when it hit the ground, it is more likely pieces, starting with the arms, dropped away. The legs and ankles might have even remained in position following the quake.

"Even as it lies," wrote Pliny, "it excites our wonder and admiration. Few men can clasp the thumb in their arms, and its fingers are larger than most statues. Where the limbs are broken asunder, vast caverns are seen yawning in the interior. Within it, too, are to be seen large masses of rock, by the weight of which the artist steadied it while erecting it."

It is said that the Egyptian king, Ptolemy III, offered to pay for its reconstruction, but the people of Rhodes refused his help. They had consulted the oracle of Delphi and feared that somehow the statue had offended the god Helios, who used the earthquake to throw it down.

In the seventh century A.D., the Arabs conquered Rhodes and broke the remains of the Colossus up into smaller pieces and sold it as scrap metal. Legend says it took 900 camels to carry away the pieces. A sad end for what must have been a majestic work of art.

The size of the Colossus was similar to that of the Statue of Liberty, but the Liberty has a higher pedestal.

Great Lighthouse at Alexandria

Seven Quick Facts |

| Location: Alexandria, Egypt. |

| Built: Around 290 - 270 BC |

Function: Guide Ships to Alexandria's Harbor. |

| Destroyed: 1303 AD by earthquake. |

| Size: Height 450 ft. (140m) |

| Made of: Stone faced with white marble blocks with lead mortar. |

| Other: Said to be the only ancient wonder with a practical application. |

Video: A Climb Up the Pharos Lighthouse

In the fall of 1994 a team of archaeological divers donned scuba equipment and entered the waters off of Alexandria, Egypt. Working beneath the surface, they searched the bottom of the sea for artifacts. Large underwater blocks of stone and remnants of sculpture were marked with floating masts so that an electronic distance measurement station on shore could obtain their exact positions. Global positioning satellites were then used to further fix the locations. The information was then fed into computers to create a detailed database of the sea floor.

Ironically, these scientists were using some of the most high-tech devices available at the end of the 20th century to try and sort out the ruins of one of the most advanced technological achievements of the 3rd century, B.C.. It was the Pharos, the great lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Alexander the Great

The story of the Pharos starts with the founding of the city of Alexandria by the Macedonian conqueror Alexander the Great in 332 B.C.. Alexander started at least 17 cities named Alexandria at different locations in his vast domain. Most of them disappeared, but Alexandria in Egypt thrived for many centuries and is prosperous even today.

Alexander the Great chose the location of his new city carefully. Instead of building it on the Nile delta, he selected a site some twenty miles to the west, so that the silt and mud carried by the river would not block the city harbor. South of the city was the marshy Lake Mareotis. After a canal was constructed between the lake and the Nile, the city had two harbors: one for Nile River traffic, and the other for Mediterranean Sea trade. Both harbors would remain deep and clear and the activity they allowed made the city very wealthy.

A modern lighthouse often is designed as just a single, slim column, unlike the Pharos. Alexander died in 323 B.C. and the city was completed by Ptolemy Soter, the new ruler of Egypt. Under Ptolemy the city became rich and prosperous. However, it needed both a symbol and a mechanism to guide the many trade ships into its busy harbor. Ptolemy authorized the building of the Pharos in 290 B.C., and when it was completed some twenty years later, it was the first lighthouse in the world and the tallest building in existence, with the exception of the Great Pyramid. The construction cost was said to have been 800 talents, an amount equal today to about three million dollars.

Construction of the Lighthouse

The lighthouse's designer is believed to be Sostratus of Knidos (or Cnidus), though some sources argue he only provided the financing for the project. Proud of his work, Sostratus desired to have his name carved into the foundation. Ptolemy II, the son who ruled Egypt after his father, refused this request, wanting only his own name to be on the building. A clever man, Sostratus supposedly had the inscription:

SOSTRATUS SON OF DEXIPHANES OF KNIDOS ON BEHALF OF ALL MARINERS TO THE SAVIOR GODS

chiseled into the foundation, then covered it with plaster. Into the plaster was carved Ptolemy's name. As the years went by (and after both the death of Sostratus and Ptolemy) the plaster aged and chipped away, revealing Sostratus' dedication.

The lighthouse was built on the island of Pharos and soon the building itself acquired that name. The connection of the name with the function became so strong that the word "Pharos" became the root of the word "lighthouse" in the French, Italian, Spanish and Romanian languages.

There are two detailed descriptions made of the lighthouse in the 10th century A.D. by Moorish travelers Idrisi and Yusuf Ibn al-Shaikh. According to their accounts, the building was 300 cubits high. Because the cubit measurement varied from place to place, however, this could mean that the Pharos stood anywhere from 450 (140m) to 600 (183m) feet in height, although the lower figure is much more likely.

The design was unlike the slim single column of most modern lighthouses, but more like the structure of an early twentieth century skyscraper. There were three stages, each built on top of one other. The building material was stone faced with white marble blocks cemented together with lead mortar. The lowest level of the building, which sat on a 20 foot (6m) high stone platform, was probably about 240 feet (73m) in height and 100 feet (30m) square at the base, shaped like a massive box. The door to this section of the building wasn't at the bottom of the structure, but part way up and reached by a 600 foot (183m) long ramp supported by massive arches. Inside this portion of the structure was a large spiral ramp that allowed materials to be pulled to the top in animal-drawn carts.

On top of that first section was an eight-sided tower which was probably about 115 feet (35m) in height. On top of the tower was a cylinder that extended up another 60 feet (18m) to an open cupola where the fire that provided the light burned. On the roof of the cupola was a large statue, probably of the god of the sea, Poseidon.

The Mirror

A depiction of the lighthouse by the 16th-century Dutch artist Maarten van Heemskerck The interior of the upper two sections had a shaft with a dumbwaiter that was used to transport fuel up to the fire. Staircases allowed visitors and the keepers to climb to the beacon chamber. There, according to reports, a large curved mirror, perhaps made of polished bronze, was used to project the fire's light into a beam. It was said ships could detect the light from the tower at night or the smoke from the fire during the day up to one-hundred miles away.

There are stories that this mirror could be used as a weapon to concentrate the sun and set enemy ships ablaze as they approached. Another tale says that it was possible to use the mirror to magnify the image of the city of Constantinople, which was located far across the sea, and observe what was going on there. Both of these stories seem implausible, however.

The structure was said to be liberally decorated with statuary including four likenesses of the god Triton on each of the four corners of the roof of the lowest level. Materials recently salvaged from the sea by archeologists, including the stone torso of a woman, seem to support these stories.

The lighthouse was apparently a tourist attraction. Food was sold to visitors at the observation platform at the top of the first level. A smaller balcony provided an outlook from the top of the eight-sided tower for those that wanted to make the additional climb. The view from there must have been impressive as it was probably 300 feet above the sea. There were few places in the ancient world where a person could ascend a man-made tower to get such a perspective.

Destruction

How then did the world's first lighthouse wind up on the floor of the Mediterranean Sea? Most accounts indicate that it, like many other ancient buildings, was the victim of earthquakes. It stood for over 1,500 years, apparently surviving a tsunami that hit eastern Mediterranean in 365 AD with minor damage. After that, however, tremors might have been responsible for cracks that appeared in the structure at the end of the10th century and required a restoration that lowered the height of the building by about 70 feet. Then in 1303 A.D., a major earthquake shook the region that put the Pharos permanently out of business. Egyptian records indicate the final collapse occurred in 1375, though ruins remained on the site for some time until 1480 when much of the building's stone was used to construct a fortress on the island that still stands today.

There is also an unlikely tale that part of the lighthouse was demolished through trickery. In 850 A.D. it is said that the Emperor of Constantinople, a rival port, devised a clever plot to get rid of the Pharos. He spread rumors that there was a fabulous teasure buried under the lighthouse. When the Caliph at Cairo, who controlled Alexandria at this time heard these rumors, he ordered that the tower be pulled down to get at the treasure. It was only after the great mirror had been destroyed and the top two portions of the tower removed that the Caliph realized he'd been deceived. He tried to rebuild the tower, but couldn't, so he turned it into a mosque instead.

As colorful as this story is there does not seem to be much truth in it. Visitors in 1115 A.D. reported the Pharos intact and still operating as a lighthouse.

Did the divers actually find the remains of Pharos in the bottom of the harbor? Some of the larger blocks of stone found certainly seem to have come from a huge building. Statues were located that may have stood at the base of the Pharos. Interestingly enough, much of the material found seems to be from earlier eras than the lighthouse. Scientists speculate that these may have been recycled in the construction of the Pharos from an even older building.

The area is now an underwater archaeological park. Tourists with diving gear can swim about the remains of the great Pharos lighthouse while they wonder what it would have been like to climb to its ancient heights a thousand years ago.

An ancient coin depicting the lighthouse.

No comments:

Post a Comment