Great Pyramid of Giza

(Courtesy Nina Aldin Thune and Creative Commons)

Seven Quick Facts |

| Location: Giza, Egypt |

| Built: Around 2560 BC |

| Function: Tomb of Pharoah Khufu |

| Destroyed: Still stands today. |

| Size: Height 480 ft. (146m) |

| Made of: Mostly limestone |

| Other: Tallest building in the world till 1311 AD and again from 1647 to 1874. |

Video: Building the Great Pyramid

It's 756 feet long on each side, 450 feet high and is composed of 2,300,000 blocks of stone, each averaging 2 1/2 tons in weight. Despite the makers' limited surveying tools, no side is more than 8 inches different in length than another, and the whole structure is perfectly oriented to the points of the compass. Even in the 19th century, it was the tallest building in the world and, at the age of 4,500 years, it is the only one of the famous "Seven Wonders of the Ancient World" that still stands. Even today it remains the most massive building on Earth. It is the Great Pyramid of Khufu, at Giza, Egypt.

Some of the earliest history of the Pyramid comes from a Greek the historian and traveler Herodotus of Halicanassus. He visited Egypt around 450 BC and included a description of the Great Pyramid in a history book he wrote. Herodotus was told by his Egyptian guides that it took twenty years for a force of 100,000 oppressed slaves to build the pyramid (with another 10 years to build a stone causeway that connected it to a temple in the valley below). Stones were lifted into position by the use of immense machines. The purpose of the structure, according to Herodotus's sources, was as a tomb for the Pharaoh Khufu (whom the Greeks referred to as Cheops).

Herodotus, a Greek from the democratic city of Athens, probably found the idea of a single man employing such staggering wealth and effort on his tomb an incredible act of egotism. He reported that even thousands of years later the Egyptians still hated Khufu for the burden he had placed on the people and could hardly bring themselves to speak his name.

However, Khufu's contemporary Egyptian subjects may have seen the great pyramid in a different light. To them the pharaoh was not just a king, but a living god who linked their lives with those of the immortals. The pyramid, as an eternal tomb for the pharaoh's body, may have offered the people reassurance of his continuing influence with the gods. The pyramid wasn't just a symbol of regal power, but a visible link between earth and heaven.

Indeed, many of the stories Herodotus relates to us are probably false. Engineers calculate that fewer men and less years were needed than Herodotus suggests to build the structure. It also seems unlikely that slaves or complicated machines were needed for thepyramid's construction. It isn't surprising that the Greek historian got it wrong, however. By the time he visited the site, the structure was already 20 centuries old, and much of the truth about it was shrouded in the mists of history.

Certainly the idea that it was a tomb for a Pharaoh, though, seems in line with Egyptian practices. For many centuries before and after the construction of the Great Pyramid, the Egyptians had interned their dead Pharaoh-Kings, whom they believed to be living Gods, in intricate tombs. Some were above-ground structures, like the pyramid, others were cut in the rock underground. All the dead leaders were outfitted with the many things it was believed they would need in the afterlife to come. Many were buried with untold treasures.

The Pyramid Complex

If we were to visit the location of the great pyramid when it was just finished, it would look very different than we see it today. Originally, the pyramid itself was encased in highly polished white limestone with a smooth surface which is now gone. At the very top of the structure would have been a capstone, which is also now missing. Some sources suggest that the capstone might have been sheathed in gold. Between the white limestone and the golden cap the pyramid would have made an impressive sight shining in the bright Egyptian sun.

Around the base of the great pyramid were four smaller pyramids, three of which still stand today. On the east side of the pyramid stood a now missing Funerary temple. Running down the hill into the valley was a stone causeway, which linked the Funerary temple with a temple in the valley. Around the pyramid were six boat shaped pits that may have contained the hulls of vessels that belonged to the pharaoh. Parts of one of these have been found and reconstructed into a 147 foot long boat that today is enclosed next to the pyramid in its own museum.

The other two large pyramids at Giza, the Pyramid of Khafre (Khufu's son) and the Pyramid of Menkaure had not yet been built, so the Khufu's pyramid and its associated structures stood alone, though surrounded by the dwelling places and the graves of many of those that helped construct it.

Opening the Pyramid

Even in ancient times, thieves breaking into the sacred burial places were a major problem and Egyptian architects became adept at designing solutions to this problem. They built passageways that could be plugged with impassable granite blocks; created secret, hidden rooms and made decoy chambers. No matter how clever the designers became, however, robbers seemed to be even smarter and with almost no exceptions, each of the great tombs of the Egyptian Kings was plundered.

In 820 A.D. the Arab Caliph Abdullah Al Manum decided to make his own search for the treasure of Khufu. He gathered a gang of workmen and, unable to find the location of a reputed secret door, started burrowing into the side of the monument. After a hundred feet of hard going they were about to give up when they heard a heavy thud echo through the interior of the pyramid. Digging in the direction of the sound, they soon came upon a passageway that descended into the heart of the structure. On the floor lay a large block that had fallen from the ceiling, apparently causing the noise they had heard. Back at the beginning of the corridor they found the secret hinged door to the outside they had missed.

Working their way down the passage they soon found themselves deep in the natural stone below the pyramid. The corridor stopped descending and went horizontal for about 50 feet, then ended in a blank wall. A pit extended downward from there for about 30 feet, but it was empty. When the workmen examined the fallen block they noticed a large granite plug above it. Cutting through the softer stone around it they found another passageway that extended up into the heart of the pyramid. As they followed this corridor upward, they found several more granite blocks closing off the tunnel. In each case they cut around them by burrowing through the softer limestone of the walls. Finally, they found themselves in a low, horizontal passage that led to a small, square, empty room. This became known as the "Queen's Chamber," though it seems unlikely that it ever served that function.

Back at the junction of the ascending and descending passageways, the workers noticed an open space in the ceiling. Climbing up they found themselves in a high-roofed, ascending passageway. This became known as the "Grand Gallery." At the top of the gallery was a low, horizontal passage that led to a large room, some 34 feet long, 17 feet wide, and 19 feet high. It became known as the "King's Chamber." In the center was a huge granite sarcophagus without a lid. Otherwise the room was completely empty.

The Missing Treasure

The Arabs, as if in revenge for the missing treasure, stripped the pyramid of its fine white limestone casing and used it for building in Cairo. They even attempted to disassemble the great pyramid itself, but after removing the top 30 feet of stone, they gave up on this impossible task.

So what happened to the treasure of King Khufu? Conventional wisdom says that, like so many other royal tombs, the pyramid was the victim of robbers in ancient times. If we believe the accounts of Manum's men, though, the granite plugs that blocked the passageways were still in place when they entered the tomb. How did the thieves get in and out?

In 1638 an English mathematician, John Greaves, visited the pyramid. He discovered a narrow shaft, hidden in the wall that connected the Grand Gallery with the descending passage. Both ends were tightly sealed and the bottom was blocked with debris. Some archaeologists have suggested this route was used by the last of the Pharaoh's men to exit the tomb after the granite plugs had been put in place and by the thieves to get inside. Given the small size of the passageway and the amount of debris it seems unlikely that the massive amount of treasure, including the huge missing sarcophagus lid, could have been removed this way, however.

Construction

Scientists have long argued about how this massive structure was built, but the most likely theory seems to be that the Egyptians built a huge ramp that allowed them to drag the blocks into position. Because a single straight ramp (as seen in the recent movie10,000B.C.) would have to be over a half mile long to reach the top and would need to contain as much material as the pyramid itself, engineers have suggested that the ramp was in the shape of a spiral running around the outside of the pyramid. Alternately the Egyptians may have combined a straight ramp that ran part way up the pyramid with a spiral ramp to the very top levels. Blocks were probably dragged up the ramp by a team of men and put into their final position through the use of levers (For more information on the construction of the Great Pyramid, see our page How to Build a Pyramid).

French architect Jean-Pierre Houdin advanced the theory that a spiral ramp was used on the inside of the pyramid to move the stone blocks. According to Houdin a straight external ramp was used to get materials to the 140 foot level. From there workers dragged the stones through a set of gently rising tunnels just inside the outer walls. The last tunnel would exit on the monument's top. A 1986 microgravity survey of the pyramid discovered a peculiar anomaly: a less-dense structure in the form of a spiral within the pyramid that may turn out to be what is left of Houdin's tunnels.

A project management group that studied the problem of building the Great Pyramid estimated that the project, using material and methods available at the time, might have required less than ten years to complete: Two or three years site preparation, five years of actual construction and two years to remove the ramps and put on the finishing touches. This could have been done with an average work force of less than 14,000 laborers and a peak force of 40,000. By examining the ruins of dwellings and workshops in the area, archeologists have estimated between 4,000 and 5,000 of these men were full-time workers committed to the project through most of the construction.

Egyptian records indicate that the laborers, while being drafted against their will, were actually well cared for by ancient standards. Regulations have been found covering the maximum amount of work allowed per day, the wages received and holidays each worker was entitled to. Also, by scheduling most of the work to be done during annual flood periods, the Pharaoh could get a lot done without impacting the normal Egyptian economy.

Was the Pyramid a Tomb?

Some have suggested that the pyramid was never meant as a tomb, but as an astronomical observatory. The Roman author Proclus, in fact, states that before the pyramid was completed it did serve in this function. We can't put too much weight on Proclus words, though, remembering that when he advanced his theory the pyramid was already over 2000 years old.

Richard Proctor, an astronomer, did observe that the descending passage could have been used to observe the transits of certain stars. He also suggested that the grand gallery, when open at the top during construction, could have been used for mapping the sky.

Many strange (and some silly) theories have arisen over the years to explain the pyramid and its passageways. Most archaeologists, however, accept the theory that the great pyramid was just the largest of a tradition of tombs used for the Pharaohs of Egypt.

So what happened to Khufu's mummy and treasure? Nobody knows. Extensive explorations have found no other chambers or passageways. Still one must wonder if, perhaps in this one case, the King and his architects outsmarted both the ancient thieves and modern archaeologists and that somewhere in, or below, the last wonder of the ancient world, rests Khufu and his sacred gold.

Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Seven Quick Facts |

| Location: City State of Babylon (Modern Iraq) |

| Built: Around 600 BC |

| Function: Royal Gardens |

| Destroyed: Earthquake, 2nd Century BC |

| Size: Height probably 80 ft. (24m) |

| Made of: Mud brick waterproofed with lead. |

| Other: Some archeologists suggest that the actual location was not in Babylon, but 350 miles to the north in the city of Nineveh. |

Video: Gift for a Queen: The Hanging Gardens

The city of Babylon, under King Nebuchadnezzar II, must have been a wonder to the ancient traveler's eyes. "In addition to its size," wrote Herodotus, a Greek historian in 450 BC, "Babylon surpasses in splendor any city in the known world."

Herodotus claimed the outer walls were 56 miles in length, 80 feet thick and 320 feet high. Wide enough, he said, to allow two four-horse chariots to pass each other. The city also had inner walls which were "not so thick as the first, but hardly less strong." Inside these double walls were fortresses and temples containing immense statues of solid gold. Rising above the city was the famous Tower of Babel, a temple to the god Marduk, that seemed to reach to the heavens.

While archaeological excavations have disputed some of Herodotus's claims (the outer walls seem to be only 10 miles long and not nearly as high) his narrative does give us a sense of how awesome the features of the city appeared to those ancients that visited it. Strangely, however, one of the city's most spectacular sites is not even mentioned by Herodotus: The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Gift for A Homesick Wife

Accounts indicate that the garden was built by King Nebuchadnezzar, who ruled the city for 43 years starting in 605 BC (There is an alternative story that the gardens were built by the Assyrian Queen Semiramis during her five year reign starting in 810 BC). This was the height of the city's power and influence and King Nebuchadnezzar is known to have constructed an astonishing array of temples, streets, palaces and walls.

According to accounts, the gardens were built to cheer up Nebuchadnezzar's homesick wife, Amyitis. Amyitis, daughter of the king of the Medes, was married to Nebuchadnezzar to create an alliance between the two nations. The land she came from, though, was green, rugged and mountainous, and she found the flat, sun-baked terrain of Mesopotamia depressing. The king decided to relieve her depression by recreating her homeland through the building of an artificial mountain with rooftop gardens.

The Hanging Gardens probably did not really "hang" in the sense of being suspended from cables or ropes. The name comes from an inexact translation of the Greek word kremastos, or the Latin wordpensilis, which means not just "hanging", but "overhanging" as in the case of a terrace or balcony.

The Greek geographer Strabo, who described the gardens in first century BC, wrote, "It consists of vaulted terraces raised one above another, and resting upon cube-shaped pillars. These are hollow and filled with earth to allow trees of the largest size to be planted. The pillars, the vaults, and terraces are constructed of baked brick and asphalt."

"The ascent to the highest story is by stairs, and at their side are water engines, by means of which persons, appointed expressly for the purpose, are continually employed in raising water from the Euphrates into the garden."

The Water Problem

Strabo touches on what, to the ancients, was probably the most amazing part of the garden. Babylon rarely received rain and for the garden to survive, it would have had to been irrigated by using water from the nearby Euphrates River. That meant lifting the water far into the air so it could flow down through the terraces, watering the plants at each level. This was an immense task given the lack of modern engines and pressure pumps in the fifth century B.C.. One of the solutions the designers of the garden may have used to move the water, however, was a "chain pump."

A chain pump is two large wheels, one above the other, connected by a chain. On the chain are hung buckets. Below the bottom wheel is a pool with the water source. As the wheel is turned, the buckets dip into the pool and pick up water. The chain then lifts them to the upper wheel, where the buckets are tipped and dumped into an upper pool. The chain then carries the empty buckets back down to be refilled.

The pool at the top of the gardens could then be released by gates into channels which acted as artificial streams to water the gardens. The pump wheel below was attached to a shaft and a handle. By turning the handle, slaves provided the power to run the contraption.

An alternate method of getting the water to the top of the gardens might have been a screw pump. This device looks like a trough with one end in the lower pool from which the water is taken with the other end overhanging an upper pool to which the water is being lifted. Fitting tightly into the trough is a long screw. As the screw is turned, water is caught between the blades of the screw and forced upwards. When it reaches the top, it falls into the upper pool.

Turning the screw can be done by a hand crank. A different design of screw pump mounts the screw inside a tube, which takes the place of the trough. In this case the tube and screw turn together to carry the water upward.

Screw pumps are very efficient ways of moving water and a number of engineers have speculated that they were used in the Hanging Gardens. Strabo even makes a reference in his narrative of the garden that might be taken as a description of such a pump. One problem with this theory, however, is that there seems to be little evidence that the screw pump was around before the Greek engineer Archimedes of Syracuse supposedly invented it around 250 B.C., more than 300 years later.

Garden Construction

Construction of the garden wasn't only complicated by getting the water up to the top, but also by having to avoid having the liquid ruining the foundations once it was released. Since stone was difficult to get on the Mesopotamian plain, most of the architecture in Babel utilized brick. The bricks were composed of clay mixed with chopped straw and baked in the sun. These were then joined with bitumen, a slimy substance, which acted as a mortar. Unfortunately, because of the materials they were made of, the bricks quickly dissolved when soaked with water. For most buildings in Babel this wasn't a problem because rain was so rare. However, the gardens were continually exposed to irrigation and the foundation had to be protected.

Diodorus Siculus, a Greek historian, stated that the platforms on which the garden stood consisted of huge slabs of stone (otherwise unheard of in Babel), covered with layers of reed, asphalt and tiles. Over this was put "a covering with sheets of lead, that the wet which drenched through the earth might not rot the foundation. Upon all these was laid earth of a convenient depth, sufficient for the growth of the greatest trees. When the soil was laid even and smooth, it was planted with all sorts of trees, which both for greatness and beauty might delight the spectators."

How big were the gardens? Diodorus tells us they were about 400 feet wide by 400 feet long and more than 80 feet high. Other accounts indicate the height was equal to the outer city walls, walls that Herodotus said were 320 feet high. In any case the gardens were an amazing sight: A green, leafy, artificial mountain rising off the plain.

Were the Hanging Gardens Actually in Nineveh?

But did they actually exist? Some historians argue that the gardens were only a fictional creation because they do not appear in a list of Babylonian monuments composed during that period. It is also a possibility they were mixed up with another set of gardens built by King Sennacherib in the city of Nineveh around 700 B.C..

Stephanie Dalley, an Oxford University Assyriologist, thinks that earlier sources were translated incorrectly putting the gardens about 350 miles south of their actual location at Nineveh. King Sennacherib left a number of records describing a luxurious set of gardens he'd built there in conjunction with an extensive irrigation system. In contrast Nebuchadrezzar makes no mention of gardens in his list of accomplishments at Babylon. Dalley also argues that the name "Babylon" which means "Gate of the Gods" was a title that could be applied to several Mesopotamian cities. Sennacherib apparently renamed his city gates after gods suggesting that he wished Nineveh to be considered "a Babylon" too, creating confusion.

Archaeological Search

These were probably some of the questions that occurred to German archaeologist Robert Koldewey in 1899. For centuries the ancient city of Babel had been nothing but a mound of muddy debris never explored by scientists. Though unlike many ancient locations, the city's position was well-known, nothing visible remained of its architecture. Koldewey dug on the Babel site for some fourteen years and unearthed many of its features including the outer walls, inner walls, foundation of the Tower of Babel, Nebuchadnezzar's palaces and the wide processional roadway which passed through the heart of the city.

While excavating the Southern Citadel, Koldewey discovered a basement with fourteen large rooms with stone arch ceilings. Ancient records indicated that only two locations in the city had made use of stone, the north wall of the Northern Citadel, and the Hanging Gardens. The north wall of the Northern Citadel had already been found and had, indeed, contained stone. This made Koldewey think that he had found the cellar of the gardens.

He continued exploring the area and discovered many of the features reported by Diodorus. Finally, a room was unearthed with three large, strange holes in the floor. Koldewey concluded this had been the location of the chain pumps that raised the water to the garden's roof.

The foundations that Koldewey discovered measured some 100 by 150 feet. This was smaller than the measurements described by ancient historians, but still impressive.

While Koldewey was convinced he'd found the gardens, some modern archaeologists call his discovery into question, arguing that this location is too far from the river to have been irrigated with the amount of water that would have been required. Also, tablets recently found at the site suggest that the location was used for administrative and storage purposes, not as a pleasure garden.

If they did exist, what happened to the gardens? There is a report that they were destroyed by an earthquake in the second century B.C.. If so, the jumbled remains, mostly made of mud-brick, probably slowly eroded away with the infrequent rains.

Whatever the fate of the gardens were, we can only wonder if Queen Amyitis was happy with her fantastic present, or if she continued to pine for the green mountains of her distant homeland.

Statue of Zeus at Olympia

Seven Quick Facts |

| Location: Peloponnesus (Modern Greece) |

| Built: Around 432 BC |

| Function: Shine to Greek God Zeus |

| Destroyed: Fire 5th Century A.D. |

| Size: Height around 40 ft. (12m) |

| Made of: Ivory and gold-plated plates on wooden frame. |

| Other: Remains of the workshop where it was built was found during an excavation in the 1950's |

Video: Quick Look at the Statue of Zeus

n ancient times one of the Greeks most mportant festivals, the Olympic Games, was held every four years in honor of the King of their gods, Zeus. Like our modern Olympics, athletes traveled from distant lands, including Asia Minor, Syria, Egypt and Sicily, to compete. The Olympics were first started in 776 B.C. and held at a shrine to Zeus located on the western coast of Greece in a region called Peloponnesus. The games helped to unify the Greek city-states and a sacred truce was declared. Safe passage was given to all traveling to the site, called Olympia, for the season of the games.

The Temple at Olympia

The site consisted of a stadium - where the competitions were actually done - and a sacred grove, or Altis, where a number of temples were located. The shrine to Zeus here was simple in the early years, but as time went by and the games increased in importance, it became obvious that a new, larger temple, one worthy of the King of the gods, was needed. Between 470 and 460 B.C., construction on a new temple was started. The designer was Libon of Elis and his masterpiece, The Temple of Zeus, was completed in 456 B.C..

This temple followed a design used on many large Grecian temples. It was similar to the Parthenon in Athens and the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus. The temple was built on a raised, rectangular platform. Thirteen large columns supported the roof along the sides and six supported it on each end. A gently-peaked roof topped the building. The triangles, or "pediments," created by the sloped roof at the ends of the building were filled with sculpture. Under the pediments, just above the columns, was more sculpture depicting the twelve labors of Heracles, six on each end of the temple.

Though the temple was considered one of the best examples of the Doric design because of its style and the quality of the workmanship, it was decided the temple alone was too simple to be worthy of the King of the gods. To remedy this, a statue was commissioned for the interior. It would be a magnificent statue of Zeus that would become one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

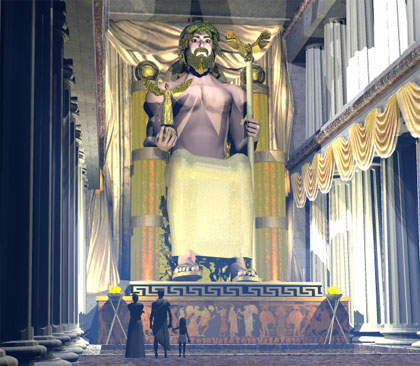

A Statue Worthy of the King of the Gods

The sculptor chosen for this great task was a man named Phidias. He had already rendered a forty-foot high statue of the goddess Athena for the Parthenon in Athens and had also done much of the sculpture on the exterior of that temple. After his work in Athens was done, Phidias traveled to Olympia around 432 B.C. to start on what was to be considered his best work, the statue of Zeus. On arriving he set up a workshop to the west of the temple. He would take the next 12 years to complete the project.

According to accounts, the statue when finished was located at the western end of the temple. It was 22 feet wide and more than 40 feet tall. The figure of Zeus was seated on an elaborate throne. His head nearly grazed the roof. The historian Strabo wrote, "...although the temple itself is very large, the sculptor is criticized for not having appreciated the correct proportions. He has depicted Zeus seated, but with the head almost touching the ceiling, so that we have the impression that if Zeus moved to stand up he would unroof the temple..."

Others who viewed that temple disagreed with Strabo and found the proportions very effective in conveying the god's size and power. By filling nearly all the available space, the statue was made to seem even larger than it really was.

Philo of Byzantium, who wrote about all of the wonders, was certainly impressed. "Whereas we just wonder at the other six wonders, we kneel in front of this one in reverence, because the execution of the skill is as incredible as the image of Zeus is holy…"

In 97 A.D. another visitor Dio Crysostomos declared the image was so powerful that, "If a man, with a heavy heart from grief and sorrow in life, will stand in front of the statue, he will forget all these."

In his right hand the statue held the figure of Nike (the goddess of victory) and in its left was a scepter "inlaid with every kind of metal..." which was topped with an eagle. Perhaps even more impressive than the statue itself was the throne made out of gold, ebony, ivory and inlaid with precious stones. Carved into the chair were figures of Greek gods and mystical animals, including the half man/half lion sphinx.

Construction of the Statue

The figure's skin was composed of ivory and the beard, hair and robe of gold. Construction was by a technique known as chryselephantine where gold-plated bronze and ivory sections were attached to a wooden frame. Because the weather in Olympia was so damp, the statue required care so that the humidity would not crack the ivory. It is said that for centuries the decedents of Phidias held the responsibility for this maintenance. To keep it in good shape the statue was constantly treated with olive oil kept in a special reservoir in the floor of the temple that also served as a reflecting pool. Light reflected off the pool from the doorway may also have had the effect of illuminating the statue.

The Greek traveler Pausanias recorded that when the statue was finally completed, Pheidias asked Zeus for a sign that the work was to his liking. The god replied by touching the temple with a thunderbolt that did no damage. According to the account a bronze hydria (water vessel) was placed at the spot where the thunderbolt hit the structure.

Besides the statue, there was little inside the temple. The Greeks preferred the interior of their shrines to be simple. The feeling it gave was probably very much like the Lincoln Memorial or Jefferson Memorial with their lofty marble columns and single, large statues. However with a height greater than 40 feet, the statue of Zesus was more than twice as tall as Lincoln's likeness at his memorial on the mall in Washington D.C..

Copies of the statue were made, but none survive, though pictures found on coins give researchers clues about its appearance.

Despite his magnificent work at Olympia, Phidias ran into trouble when he returned home. He was a close friend with Pericles, who ruled the Athens. Enemies of Pericles, unable to strike at the ruler directly, attacked his friends instead. Phidias was accused of stealing gold meant for the statue of Athena. When that charge failed to stick, they claimed he had carved his image, and that of Pericles into the sculpture found on the Parthenon. This would have been improper in the Greeks' eyes and Phidias was thrown into jail where he died awaiting trial.

His masterpiece lived on, however. It was damaged in an earthquake in 170 B.C. and repaired. However, much of its grandeur was probably lost after Emperor Constantine decreed that gold be stripped from all pagan shrines after he converted to Christianity in the early fourth century A.D.. Then in 392 A.D. the Olympics were abolished by Emperor Theodosius I of Rome, a Christian who saw the games as a pagan rite. After that according to the Byzantine historian Georgios Kedrenos, the statue was moved by a wealthy Greek named Lausus to the city of Constantinople where it became part of his private collection of classical art. It is believed that the remains of the statue were destroyed by a fire that swept the city in 475 A.D.. However, other sources say the statue was still at the Olympic Temple when it burned down in 425 A.D..

Modern Excavations

The first archaeological work on the Olympia site was done by a group of French scientists in 1829. They were able to locate the outlines of the temple and found fragments of the sculpture showing the labors of Heracles. These pieces were shipped to Paris where they are still on display today at the Louvre.

The next expedition came from Germany in 1875 worked at Olympia for five summers. Over that period they were able to map out most of the buildings there, discovered more fragments of the temple's sculpture, and located the remains of the pool in the floor that contained the oil for the statue.

In the 1950's an excavation uncovered the workshop of Phidias which was discovered beneath an early Christian Church. Archaeologists found sculptor's tools, a pit for casting bronze, clay molds, modeling plaster and even a portion of one of the elephant's tusks which had supplied the ivory for the statue. Many of the clay molds, which had been used to shape the gold plates, bore serial numbers which must have been used to show the place of the plates in the design.

A 19th century expedition poses on the jumbled ruins of the Temple of Zeus. Today the stadium at the site has been restored. Little is left of the temple, though, except a few jumbled columns on the ground. Of the statue, which was perhaps the most wonderful work at Olympia, all is now completely gone.

Temple of Artemis at Ephesus

Seven Quick Facts |

| Location: Ephesus (Present day Turkey) |

| Built: Around 323 BC |

| Function: Temple to Goddess Artemis |

| Destroyed: 262 AD by Goths |

| Size: Length 425 ft. (129m) |

| Made of: Mostly marble |

| Other: Largest in a series of temples to Artemis on this site. |

Video: Temple of Ephesus

800 years after its destruction, the magnificent Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, had been completely forgotten by the people of the town that had once held it in such pride.

And there is no doubt that the temple was indeed magnificent. "I have seen the walls and Hanging Gardens of ancient Babylon," wrote Philon of Byzantium, "the statue of Olympian Zeus, the Colossus of Rhodes, the mighty work of the high Pyramids and the tomb of Mausolus. But when I saw the temple at Ephesus rising to the clouds, all these other wonders were put in the shade."

So what happened to this great temple? And what happened to the city that hosted it? What turned Ephesus from a busy port of trade to a few shacks in a swamp?

The Shrine to the Goddess Artemis

The first shrine to the Goddess Artemis was probably built around 800 B.C. on a marshy strip near the river at Ephesus. The Ephesus goddess Artemis, sometimes called Diana, is not quite the same figure as was worshiped in Greece. The Greek Artemis was the goddess of the hunt. The Ephesus Artemis was a goddess of fertility and was often pictured as draped with eggs or multiple breasts, symbols of fertility, from her waist to her shoulders.

That earliest temple contained a sacred stone, probably a meteorite, that had "fallen from Jupiter." The shrine was destroyed and rebuilt several times over the next few hundred years. By 600 B.C., the city of Ephesus had become a major port of trade and an architect named Chersiphron was engaged to build a new, larger temple. He designed it with high stone columns. Concerned that carts carrying the columns might get mired in the swampy ground around the site, Chersiphron laid the columns on their sides and had them rolled to where they would be erected.

This temple didn't last long. According to one story in 550 B.C., King Croesus of Lydia conquered Ephesus and the other Greek cities of Asia Minor and during the fighting, the temple was destroyed. An archeological examination of the site, however, suggests that a major flood hit the temple site at about the same time and may have been the actual cause of the destruction. In either case, the victorious Croesus proved himself a gracious new ruler by contributing generously to the building of a replacement temple.

This next temple dwarfed those that had come before it. The architect is thought to be a man named Theodorus. Theodorus's temple was 300 feet in length and 150 feet wide with an area four times the size of the previous temple. More than one hundred stone columns supported a massive roof. One unusual feature of the temple was that a number of columns had bases that were carved with figures in relief.

The new temple was the pride of Ephesus until 356 B.C. when tragedy struck. A young Ephesian named Herostratus, who would stop at nothing to have his name go down in history, set fire to the wooden roof of the building. He managed to burn the structure to the ground. The citizens of Ephesus were so appalled by this act that after torturing Herostratus to death, they issued a decree that anyone who even spoke of his name would be put to death.

One of the legends that grew up about the great fire was that the night that the temple burned was the very same night that Alexander the Great was born. According to the story, the goddess Artemis was so preoccupied with Alexander's safe birth she was unable to save her own temple from its fiery destruction.

Construction of the Great Temple

Shortly after the fire, a new temple was commissioned. The architect was Scopas of Paros, one of the most famous sculptors of his day. By this point Ephesus was one of the greatest cities in Asia Minor and no expense was spared in the reconstruction. According to Pliny the Elder, a Roman historian, the new temple was a "wonderful monument of Grecian magnificence, and one that merits our genuine admiration."

The temple was built in the same wet location as before. To prepare the ground, Pliny recorded that "layers of trodden charcoal were placed beneath, with fleeces covered with wool upon the top of them." Pliny also noted that one of the reasons the builders kept the temple on its original marshy location was that they reasoned it would help protect the structure from the earthquakes which plagued the region.

The great temple is thought to be the first building completely constructed with marble. Like its predecessor, the temple had 36 columns whose lower portions were carved with figures in high-relief. The temple also housed many works of art including four bronze statues of Amazon women. The Amazons, according to myth, took refuge at Ephesus from Heracles, the Greek demigod, and founded the city.

Pliny recorded the length of this new temple at 425 feet and the width at 225 feet. Some 127 columns, 60 feet in height, supported the roof. In comparison the Parthenon, the remains of which still stand on the Acropolis in Athens today, was only 230 feet long, 100 feet wide and had 58 columns.

According to Pliny, construction took 120 years, though some experts suspect it may have only taken half that time. We do know that when Alexander the Great came to Ephesus in 333 B.C., the temple was still under construction. He offered to finance the completion of the temple if the city would credit him as the builder. The city fathers didn't want Alexander's name carved on the temple, but didn't want to tell him that. They finally gave the tactful response: "It is not fitting that one god should build a temple for another god" and Alexander didn't press the matter.

Pliny reported that earthen ramps were employed to get the heavy stone beams perched on top of the columns. This method seemed to work well until one of the largest beams was put into position above the door. It went down crookedly and the architect could find no way to get it to lie flat. He was beside himself with worry about this until he had a dream one night in which the Goddess herself appeared to him saying that he should not be concerned. She herself had moved the stone into the proper position. The next morning the architect found that the dream was true. During the night the beam had settled into its proper place.

Christianity Brings an End to Artemis Worship

The city continued to prosper over the next few hundred years and was the destination for many pilgrims coming to view the temple. A souvenir business in miniature Artemis idols, perhaps similar to a statue of her in the temple, grew up around the shrine. It was one of these business proprietors, a man named Demetrius, that gave St. Paul a difficult time when he visited the city in 57 A.D.

St. Paul came to the city to win converts to the then new religion of Christianity. He was so successful that Demetrius feared the people would turn away from Artemis and he would lose his livelihood. He called others of his trade together with him and gave a rousing speech ending with "Great is Artemis of the Ephesians!" They then seized two of Paul's companions and a near riot followed during a meeting at the city theater. Eventually, however, the city was quieted, the men released and Paul left for Macedonia.

It was Paul's Christianity that won out in the end, though. By the time the great Temple of Artemis was destroyed during a raid by the Goths in 268 A.D., both the city and the religion of Artemis were in decline. The temple was rebuilt again, but in 391 it was closed by the Roman Emperor Theodosius the Great after he made Christianity the state religion. The temple itself was destroyed by a Christian mob in 401 and the stoned was recycled into other buildings. When the Roman Emperor Constantine rebuilt much of Ephesus a century later, he declined to restore the temple. He too had become a Christian and had little interest in pagan religions.

Despite Constantine's efforts, Ephesus declined in its importance as a crossroads of trade. The bay where ships docked disappeared as silt from the river filled it. In the end what was left of the city was miles from the sea, and many of the inhabitants left the swampy lowland to live in the surrounding hills. Those that remained used the ruins of the temple as a source of building materials. Many of the fine sculptures were pounded into powder to make lime for wall plaster.

Excavations to Find the Remains

In 1863 the British Museum sent John Turtle Wood, an architect, to search for the temple. Wood met with many obstacles. The region was infested with bandits. Workers were hard to find. His budget was too small. Perhaps the biggest difficulty was that he had no idea where the temple was located. He searched for the temple for six years. Each year the British Museum threatened to cut off his funding unless he found something significant, and each year he convinced them to fund him for just one more season.

Wood kept returning to the site each year many despite hardships. During his first season he was thrown from a horse, breaking his collar bone. Two years later he was stabbed within an inch of his heart during an assassination attempt upon the British Consul in Smyrna.

Finally in 1869, at the bottom of a muddy twenty-foot deep test pit, his crew struck the base of the great temple. Wood then excavated the whole foundation removing 132,000 cubic yards of the swamp to leave a hole some 300 feet wide and 500 feet long. The remains of some of the sculptured portions of the temple were found and shipped to the British Museum where they can be viewed today.

In 1904 another British Museum expedition under the leadership of D.G. Hograth continued the excavation. Hograth found evidence of five temples on the site, each one constructed on top of the remains of another.

Today the site of the temple near the modern town of Selçuk is only a marshy field. A single column has been erected to remind visitors that once there stood in this place one of the wonders of the ancient world.

The carved base of one of the columns.

No comments:

Post a Comment